The Publicity Machine

Yesterday morning, a few hours before our dress rehearsal, I participated in ‘Midweek’, a live radio show famous for its remarkably varied participants. Libby Purves is the presenter/interviewer and she navigates a strange and contradictory terrain.

Yesterday’s guests were Jane O’Neill -a female shepherd, Jason Donovan promoting his autobiography, David Bellavia, a soldier who served in Iraq and has written a book about his experiences, and myself. By the time we had heard about a sheep shearing fest in London and Jason Donovan’s relationship with Kylie, the scene was set for Bellavia. Libby Purves cheerfully quoted some horrific passages from the book in which with brutal honesty he describes the horror of killing civilians while on duty in Fallujah.

As I gazed at and listened to this man who had been so brutalised as a cog in the war machine, struggling to retain his dignity with such phrases as the “nobility” of war – I had no desire whatsoever to talk about my work.I wanted to ask more, dig deeper, give him all possible space. But the programme rolled relentlessly on and I was asked about Carmen – the reason I had been invited onto the show. I tried at least to address the absurdity of talking about an opera so hard on the heels of someone speaking about killing in Fallujah; then talked a bit about the arts as a place where we can contemplate the extremities of experience, including death – as Carmen does - but I felt ashamed of the publicity machine which picks people up like David Bellavia, chews them up, and spits them out.

Immediately after the show I asked David Bellavia how he had felt about it. He said he had hoped writing a book would somehow be cathartic, a healing of the destruction of war, but instead found he was being forced to relive it again and again.

I could feel the depth of his pain beneath his smooth and affable exterior and tried to express my solidarity – despite our obviously quite extreme political differences (I was one of those who marched against the invasion of Iraq) -with a hug and some warm words.

Yes, sheep farming is important. Okay, Jason Donovan has written a book. And I’m directing an opera. So what? When war and government politics lead to death and mass destruction and there is a participant and witness to all that in our midst, surely we should stand aside and say: speak, and we will listen.

P.S

The dress rehearsal in the afternoon went as it should: a piece almost there; it’s as yet unresolved problems fully evident, David Kempster (Escamillo) sick and replaced an hour before curtain by his cover; and Alice delivering, heroically and miraculously, against the odds.

In the interval I went to the toilets, overheard two elderly ladies, evidently regular opera-goers, tearing the production to pieces in their high, posh voices and wondered who I was working for and why.

Continue readingRunning

The work in the studio hits the stage and I’m running. I try to answer constant questions from all members of the team whilst keeping my eye focussed on the unfolding picture.

My silent questions in the rehearsal room about how things will look when in the set, costumed, lit, and seen from a distance start to be answered.

As always, in any medium, these moments of transition from the imaginary to the real are surprising. The work starts to speak and seems to have its own identity, independent of my intention. I have to be extremely alert to this state of transformation and try to know where and how to intervene, what to change, even at this late stage, for it to reveal itself. Time is precious, every second counts, I’m writing this over a quick breakfast before another 12 hour day, and now must run again.

Continue readingLet There Be Light

I spent the weekend in the theatre. As the lovely September sun streamed down outside, we sat in the dark looking at lights.

It was my first full-on working hours with Mimi, whose lighting I have long admired, and sure enough it was a joyous experience.

When the light falls on a set for the first time, the design as first imagined, becomes visible.

Here is a walk from stage door to the stage, where I lift my eyes and my camera to the gods.

Continue readingSlow Slow, Quick Quick Slow

A rehearsal process such as this (4 weeks in the studio with the singers before attempting to stagger through the acts on stage in the Coliseum) demands incredibly detailed planning followed by very quick thinking when the plan doesn’t work as well in practice as it seemed to on paper or in the mind’s eye.

Knowing when to slow down and take a moment to observe in a detached, undefensive way what is happening in front of your eyes, is a product of experience. The temptation is to rush – to jump in and correct things immediately which are clearly not working. But if you let the ‘wrongness’ play itself out, something else emerges. The clue to how to transform a scene, an image, a moment from the pedestrian, the awkward, or the simply embarrassing to the kind of radiant clarity where it seems it could be done no other way, lies in welcoming and watching what is not right.

But to really understand why it’s not right, you have to slow down, really slow down. That moment of open-eyed observation can seem like an eternity, especially if an army of people is waiting for an instant solution to something that is so obviously wrong.

But take that moment, courageously, and genuine speed will follow, rather than panic. It’s almost like inner phrasing in the working process, a kind of breathing in what is and breathing out what it can become.

Continue readingVolver

On Friday night, in celebration after having run Act One for the first time, I put on some earrings and went out dancing with Pablo.

Such occasions are rare, these days; but since making The Tango Lesson we have managed, somehow, to meet up every few months in one city or another (Paris, New York, Oslo...) to spend an evening or two on the dance floor. Each time feels like a homecoming, expressed so eloquently in Carlos Gardel’s most famous song ‘Volver’ (“The Return”)

The feeling, like the song, is a mixture of joy and nostalgia. But however long the intervals, the dance never seems to disappear from my body, the muscle memory goes so deep.

Directing is, of course, always a look from the outside, however empathetic, however profoundly engaged. After so much mental effort, putting this production together, it is a relief to return to embodiment, and to the simple joy of dancing.

Continue readingBare Bones

As rehearsals for Carmen roll relentlessly onward, memories of earlier theatrical experiences have re-surfaced.

When Jacky Lansley and I formed Limited Dance Company in the 1970’s, one of our first productions was called Aida.

As a company of two, augmented by friends and co-conspirators, we were, naturally, attracted by the idea of the epic form. And also by the idea of the unachievable.

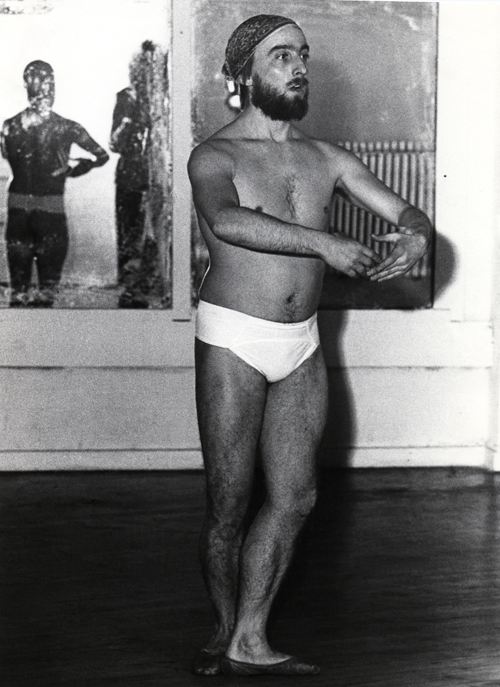

The show was set in a bare studio at Oval House Theatre, a room that had a large glass dome in the middle of its roof. A man (Craig Givens) walked in circles on the roof around the glass dome, wearing a jockstrap, a natty headscarf and black satin pointe shoes. (He was one of the few male dancers of the time brave enough and skilled enough to do pointe work). Throughout the performance, one could hear the unmistakable sound of the wooden blocks in his shoes as he repeatedly circled overhead, and see his ghostly image which was filmed on closed circuit TV and broadcast in a small monitor in the space... until, at the very end, he staggered wearily down the stairs, still on pointe, into the studio.

Meanwhile, another dancer, Fergus Early, similarly attired, was given the task of performing more pirouettes than he could ever manage, one after another, as the performance continued.

Elsewhere in the space, a female nude (Janet Krengel) sat on a pedestal reading from Das Kapital by Karl Marx.

Jacky and I were wearing voluminous dressing gowns and turbans, like backstage divas. At the climactic moment of the show, having explored other themes of the opera, we removed the dressing gowns, revealing identical ones underneath, and sang the famous duet from Aida accompanied by solo cello (played valiantly by Colin Wood).

We really did sing our hearts out, albeit in this ironic and formalized context, and as the audience laughed hysterically, some kind of minimalist operatic epic was achieved... a hymn to human fragility perhaps.

Now I am surrounded by a truly epic cast of glorious voices, soon to be performed in the largest auditorium in London, but the part of me that wanted to redefine opera back then - in a such a spare, ironic form - is still at work.

For at the core of the most complex stagings is a simple structure, and unless you search for its bones you are lost.

To Tell the Truth

I was touched to receive some messages of reassurance as "comments" after my blog about insomnia. It made me wonder whether being truthful about the feelings of doubt and vulnerability involved in any act of creation, usually hidden -- of necessity, if you are leading a large group of people -- behind a facade of directorial togetherness, is what allows people to connect with the process.

Honesty is a complicated word. Feelings are not necessarily a guide to the objective reality of how something is going. I have learned over the years to recognise signs of apparent "breakdown" in performers (i.e. tears, frustration etc) as the necessary consequence of shedding the habits and defence mechanisms which lead to certain predictable rigidities or clichéd ways of being and moving in performance. Just as an individual who habitually holds their shoulders up, when gently released from this defensive muscular pattern, may well suddenly be flooded with feelings that the tension originally blocked, a performer -- when coaxed out of familiar habits that have helped them survive the stress and exposure of a life on stage or in front of the camera -- will suddenly feel naked, alone, confused, and as if they are "not doing anything". I welcome these moments, which are often accompanied by tears. This has happened several times during the last week and the work that follows often has a beautiful clarity to it.

I too have these moments. In the last week I had shed many tears in private as my own ways of doing and being have been repeatedly challenged. It is not that I have been criticised by others: on the contrary, most of the people around me have been delightfully appreciative. But I am aiming high and deep, and am a ruthlessly stern critic of my own work. The harsh words I whisper in my own ear late at night are words I try to welcome, as a Zen student learns to welcome the blows of his master. This kind of pain is a form of awakening in which it becomes possible to locate the truth.

Continue readingPassion, Obsession, and Insomnia

Three weeks into rehearsal and I am now well into the pattern so familiar from film shoots. At the end of an impossibly long day, my mind is churning to try and digest and evaluate what has happened and simultaneously think and plan ahead for the following day (and weeks).

A mix of obsession with detail (shoes for the performers, the colour of a chair, the precise turn of a head, the disturbingly sour expression on someone's face) combines with immersion in the grand scheme (the arc of the story, the roots of the opera, the themes of jealousy and death, nostalgia and premonition) and is then joined, after a few hours fitful sleep, by jolting waves of doubt.

How can I pull it off? How can I help the huge number of performers (10 soloists 10 dancers, 56 chorus, 22 children) - so disparate in their needs, problems and experience - reach a coherent, unified and vital presence? How can I divest the production of cliché? How can I manage to get through each rehearsal session with even the minimal goal of a clear shape to it that satisfies me musically and visually?

A couple of nights ago I gave up trying to sleep at 4am, got up, made this little self-portrait and then got on with the business of planning the scene I was to rehearse that morning with the entire chorus – a fight scene.

Continue readingThe Bullfight

During our first week of work together in Spain last year Es and I decided we had to go to a bullfight. In order to understand and unravel the opera we had to experience what it was really like to watch this ‘sport’ which has been the target of so much animal rights fury; a form romanticized by Hemingway, amongst other writers, and which the ex-matador Pablo and I later met in Paris described to us, somewhat obscenely, as an ‘erotic duet’ with the bull.

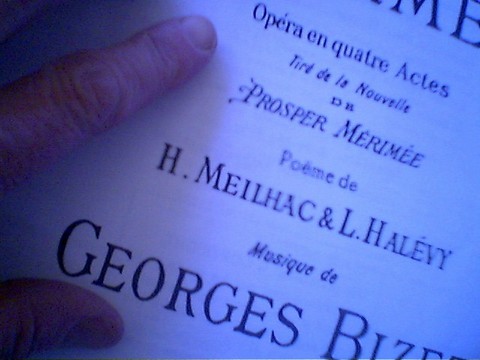

The reason we needed to research this experience is because the bullfight forms much of the central metaphor of the libretto of Carmen. It is not just the glamorous presence of Escamillo, the bullfighter in the story who's aria, the “Toreador’s song” has become so famous (an aria which Bizet himself described as ‘trash’). It is as if the entire opera is steeped in the imagery of the arena of death... an arena in which a living creature is doomed to die, while others exact ritualized moves to extinguish the beast’s wildness.

In the story it is Carmen herself, of course, who is wild and who everyone knows from the beginning (for this is a tragedy) will face extinction. But Don Jose, who eventually kills her, is, in another sense, the lumbering wounded beast who in killing her will have to face his own death as well.

As we sat in the arena in the baking hot sun, (for the seats in the shade were full) waiting for the first bull to come charging out, I started to tremble. And once the fight was underway I was often shaking and gasping so much in fear and horror at the spectacle that the camera shook beyond redemption.

But the greatest surprise for me was discovering that the entire event really seemed to be a ritualistic attempt to conquer death itself, an event in which the bull was undoubtedly the hero and the matador a strutting human doomed in his vain attempt to conquer the unconquerable (yet acting as if he had achieved it.)

The bullfight we watched was made even more horribly poignant by the fact that the ‘men’ out there were young boys. This was their first public excursion into the big arena. Their first attempt to kill. It often seemed the boys would be the ones to fall, and sometimes they did.

Their terror was palpable, however much they tried to disguise it.

But the fear of the bull was more agonizing to witness. Mute, stoic, fighting for its life: a life already lost in this ritualized context; its fate determined not by God but by man.

We emerged shaking and shaken. A couple of images from my trembling camera appear in the trailer of preparations for this production, and here are a few more moments. I can assure anyone concerned about these images that they will not be used as part of the production: but, unlike Bizet who did not feel the need to go to Spain in order to set his opera there, I felt it an absolute necessity to get behind the glamorised image of the bullfight and face its brutal reality.

For more information about the prevention of cruelty to animals visit:

PETA organises a RUNNING OF THE NUDES in Pamplona in opposition to the “Running of the Bulls” in Pamplona

Continue readingTangopera / Hiphopera

For the last two weeks we have been searching for – and finding - the dance language for Carmen.

I knew, in choosing Pablo Veron as principal dancer and co-choreographer, that the secret architecture of the tango would be central to the movement vocabulary of my production.

Not the sleazy over-dramatised tango of so many shows (the tango that the Argentineans themselves call ‘tango for export’), but the underlying forms of the dance for two that tango at its best embodies so powerfully.

From a purely choreographic point of view the many varieties of ‘enchainements’ (sequences of steps) in the tango have an extraordinary beauty and complexity and are extremely versatile as ways of moving through space.

From a dramatic point of view tango is about relationship: unity and polarity; a language of intimacy that can resemble a fight (to paraphrase Borges, the great Argentinean writer).

All of these resonances can echo and underscore the themes of Carmen.

The other major movement vocabulary that I have instinctively gravitated towards is hip hop, or street dance.

My Carmen is set in a present day urban environment, a public space that is equivalent to the ‘town square’ in the original libretto. Most of the characters in the opera are poor and disenfranchised. Street dance (like the blues) is a vital expression of those outside the system finding and creating joy and power out of nothing. A street corner can become an auditorium; as you watch young people spinning on a piece of cardboard or tumbling across tarmac you can have as powerful a visual experience as any you can see on the stage…

It turns out that Craig, one of the dancers whose vitality and fluidity so impressed me in our auditions, started his dancing life on the streets of Brixton, as I discovered this week in one of our rehearsals. To watch him and Pablo dance together, egging each other on to feats of ever greater ingenuity, has been just one of the joys of the last few days.

Put those elements together with the knowledge Kate Flatt, my other co-choreographer, has of the rhythmic patterns of gypsy and other dances from Eastern Europe, as well as the seguedilla and other Spanish dances - some of which are the same references Bizet had in his inner ear when he was composing the score - and we have the beginnings of something explosive.

These researches have all started with listening deeply to the music, which itself is dynamite, and responding to its calls.

My primary task now is to integrate these elements seamlessly into a language for the bodies on stage which will help to propel us through the narrative and be a visual counterpoint to the voices.

Our singing feet.

Continue readingJoy of the Model Box

In the early weeks of rehearsal there are lines of tape on the floor of the studio which represent the layout of the design. It’s a bit like being in Dogville by Lars von Trier – surrounded by the ghosts of a 3-dimensional space. It’s one stage of a series of imaginings of how it will be… from idea to drawings to models and eventually to the set itself.

During our working process in Spain, Es often told me how she felt about model boxes. She loves them.

I shared with her how I rarely, if ever, work with models for a film. More likely it is a location, tweaked and rearranged at the last moment, a combination of the found and the constructed. If something is to be built, there will of course be technical drawings and maybe a small model, but it is not a place where a concept evolves. It is not a place where you play. I have spent many happy and sometimes weary hours traveling in minibuses with a designer in search of THE place to shoot a scene…each rejection of a location becoming part of our process of refinement of desire, a sense of gradually grounding, coming to earth. The perfect abstract vision becoming manifest in all its lovely imperfection.

Wherever is eventually chosen, it will look different on the night (or day, or at dawn) and so the relationship between setting and scene is inevitably fluid, with a strong element of improvisation. And, crucially, there is no fixed point of view. I spend hours wandering through a space, finding how to look at it, finding where to put the camera.

The world of theatre is different. The audience is positioned on the other side of the invisible fourth wall (theatres in the round notwithstanding).

So our work at the model box, plotting and planning our universe in miniature, and all from the front, the point of view of the audience, was a new adventure for me. A necessary one, given the sheer scale of the thing and the (very) short amount of time I knew I would have to put it all together in rehearsal.

And thus, in Es’ studio, I found myself moving little model people around in a box, like a clumsy god of this tiny dolls-house world with my giant hands, grateful for the opportunity to have a dress rehearsal of sorts, an imaginary run-through in three dimensions, while Es with her now pregnant belly – another kind of house, one that had grown in tandem with our working process - clambered on chairs to manoeuvre lights from the wings.

Imaginary Spain

Bizet never went to Spain, but nevertheless felt he somehow knew it well enough to set an opera there. His Carmen, the soldiers, the urchins in the village square, the women sweating in their underwear in the cigar factory, the men longing for the women, the women longing for money, the bullfighter swaggering amongst them all; these were characters set in an imaginary landscape.

I felt that in order to begin to unravel this apparently knowable opera, Es Devlinand I had better start our working process in Spain, and separate the ‘real’ from the fictional.

I was determined that our Carmen would not fall into the trap of cliché; an operatic world of ‘pretend’. As with most operas, the music has its own integrity and authenticity, and the setting for our opera would not serve its origins well by being slavish to the settings as described in the libretto.

So we went to the house Es Devlin and her partner had bought a couple of years previously, high in the mountains with a view of the Sierra Nevada. We sat in the courtyard and talked, endlessly, stuck reference photographs on the walls, listened to the music over and over, and every evening watched another Carmen video. The sun rose and set over the dusty earth, threaded with olive trees.

We were on Spanish soil, breathing Spanish air, eating Spanish food as the production started to find form. Being in the real country released us, paradoxically, from being literal about the story we were unraveling. The secret architecture of the piece slowly became visible.

Carmen is not an opera about Spain.

Freedom and possession, certainly; the wild and the tamed; the human and the divine….you can find polarities everywhere in the story and the music. But the chocolate-box flamenco cliché of Spanishness is something the opera can do without. However, I realized that as our Carmen will be sung in English, the relationship the English speaking world has with all things Spanish would have to become part of the concept.

At the airport on the way home I browsed in the souvenir shop and bought some coasters and an ashtray decorated with bullfighting motifs, a lurid flamenco doll and a groaning toy bull to remind myself of the saturated imagery the tourist industry uses to sell an imaginary Spain to departing holidaymakers.

Warming Up

Yesterday Pablo, Lucila and I met for the first day of rehearsals in the cavernous studio at Lilian Baylis House where we will now be for the next six weeks. It will be just the three of us for this first precious week as we all - literally - find our feet. Next week we will be joined by the other dancers and the following week by the soloists, the chorus and the children. This huge barn of a space, which felt so empty yesterday, as two jet-lagged Argentineans lay down on the shiny linoleum and tried to come to earth, will gradually be filled by a hundred bodies, each finding their way into the piece.

Before moving at the speed of light, dancers need to slow down and warm up their bodies, not just to avoid injury but also as a bulwark against a tide of rising panic about the volume of work to be achieved. Of course I too need to slow down and gradually stretch to meet the task that lies ahead. (Sheer effort does not always accomplish results. I learnt that definitively during my first ballet class aged twenty one, when I discovered that however hard I tried I could not touch my toes.)

Beginning any major project – even after months of preparation – opens a Pandora’s box of questions; to what degree will the imagined production resemble the reality as it manifests, step by step? What will I need to give up, cut away, abandon? What revelations will emerge in the process? Where must I hold firm? Where must I bend, flexibly, in the storm of activity?

Terror and delight will surely accompany me in equal measure on this journey. I hope I will have the courage to be open to both.

Continue readingA Voice Called Alice

During the weeks leading up to the start of rehearsals various dramas have erupted about the translation of the libretto of Carmen into English. At root the impulse behind such dramas is entirely correct. A translation must meet various precise requirements, some of which may seem contradictory;

but the director (who has developed the interpretative concept with his or her collaborators), the conductor and the translator all need to agree about the final choice of words... their broad sweep and in detail. And, crucially, any singer must be convinced by what he or she is singing in order to be able to fully connect with it.

Translating a libretto inherently creates some problems: the words were written in the original language (French in this instance) to sound a certain way in addition to communicating a more literal meaning. And not only to sound a certain way but also to feel a certain way in the mouth. The body of the singer vibrates with the vowels and consonants, which become part of the lyricism or percussive nature of the music.

The job of the translator, then, is challenging on many levels. I will write about the joys and perils of translation in another blog. Chris Cowell (an extremely knowledgable and inventive translator) and I have been on a year-long adventure with the translation of Carmen already. But the focus of this blog lies elsewhere.

In the most recent session to work on some of the translation issues related to the character of Carmen herself, Alice Coote, Martin Fitzpatrick (head of music at the ENO), Chris Cowell and I met at my studio in East London.

As we wrestled together over one particular noun I suggested that Alice try singing the various options to see what worked in practice.

With Martin at the piano (a baby grand inherited from my beloved grandmother who herself studied singing at the Royal Academy of Music in the nineteen-twenties, gaining a silver medal), Alice - bent over her score in concentration - began to sing. As her silky, glorious vocal instrument resonated through my studio I sat very still and listened with every part of my being.

Alice was not performing; she was stopping and starting, trying this and that. But the timbre of her voice, its unique overtones and absolute integrity moved me profoundly.

So this is why I am directing Carmen, I suddenly remembered. In the struggle to find the key to the opera, to understand its roots and its evolution, in the thousand and one decisions, large and small, the inevitable crises, frustrations and setbacks, I had lost sight of the joy.

But, yes, Alice's voice is a miracle and I am blessed to be in its vicinity. When she looked up from her score and met my eyes my face was wet with tears.

Auditions

Auditions can be cruel affairs. The air is thick with fear of rejection, and the potential for humiliation is enormous.

I try to make the audition process as humane as possible but have often got it wrong. Recently, for a film, I tried having some people send in tapes of themselves reading a scene. It worked quite well. We were all saved the horror of insincere exchange. Another plus is that, later on, you can look at a performance and discuss it with colleagues with a degree of detachment that is impossible if the person is in the room.

For Carmen I had to audition opera singers for the first time in my life, one after another. I took a camera, partly as a record of the event and also to enable me to look and listen later with a little more objectivity. Audition rooms tend to be austere, unphotogenic places; uncomfortable and often harshly lit. Despite these conditions, David Kempster, singing Escamillo, held the space with a charismatic intensity. And Julian Gavin, singing in a gloomy Quaker meeting room near to ENO, gave himself entirely to the moment, singing Don Jose with as much energy as he might to an audience of thousands in a huge auditorium, Martin Fitzpatrick accompanying him at the piano and bravely singing Carmen’s lines.

Then, last month, we auditioned dancers. I found it moving to sit in a room whilst several tango couples plus about twenty men leapt and turned and sweated and gave their all in the specific way that only dancers can – a sort of full-bodied generosity.

I started the day with the dancers by explaining that the choices I would make should not be interpreted as a judgement of who was better or worse as a dancer but who was right for the particular alchemy of this production. Whether it helped people to relax or not I don’t know, but it was important to say it, as it is true.

Then, as I watched the dancers I contemplated the complex relationship between the eyes and the ears…dancers to watch, singers to listen to, on the surface, but in fact performers one and all. Individuals with bodies that are their instruments and which, with training, dedication and a kind of ruthless love, become sacred vessels.

Carmen

In 2004 I completed a film called YES. In the months that followed its release I found myself wondering if perhaps, the time had come to stop saying "No" to every offer to direct a film, commercial or opera... a policy I had stuck to since making ORLANDO.

So when I was approached by John Berry to direct CARMEN for the ENO, I only prevaricated for a year or so (!) before deciding that if I was going to direct an opera it may as well be the most popular one of all time on at least two counts: first, there is a paradoxical freedom in working with a classic – it has been done and will be done so many times that a potentially radical approach cannot possibly harm it. And, second, given my predisposition towards being a risk-taking perpetual outsider, why not dive into the heart of the mainstream – at least as far as opera is concerned?

There was another hidden factor in my decision: for many years I have nurtured the fantasy of making a musical or opera on film… I have dreamed of bringing this form - so often steeped in history and nostalgia - crackling into the present.

Perhaps CARMEN – I thought – would give me the opportunity to practice – to re-find my theatrical feet in an all-singing, all-dancing, tragic soap-opera with its roots in the arena (the Greeks and the bullfight)…

But I knew I would face many challenges.

The first would be the challenge of language.

For the ENO it would have to be a CARMEN sung in English, translated from the French, in a story which was supposed to be taking place in Spain.

The second challenge would be in part due to its popularity.

When CARMEN was first produced it was a scandalous event and perceived as a vulgar and dangerous failure. Bizet was heartbroken. It has subsequently become the safest of all operas – exoticised, familiar; everyone thinks they know who and what Carmen is.

In these circumstances how could I possibly hope to find the ‘true’ CARMEN hidden behind the cliché?

During the year after accepting the challenge the concept and design developed step by step beginning with a week in Spain with designer Es Devlin which included a close-up look at a bullfight...

Then last month I found myself with Pablo Veron in a barn in the mountains in France at the start of a choreographic adventure which included the first – I am sure – of many thrilling twists and turns which ended (as you can see in the clip at the top of this blog) in helpless laughter on the floor.

Continue reading