SALLY POTTER PRESENTS "ORLANDO" AND JOINS A ROUNDTABLE DISCUSSION WITH ULRIKE OTTINGER AND PAUL B. PRECIADO

Virginia Woolf is an author who has been championed, translated, debated and reinterpreted by various feminist and queer trends. Her work preserves something that can be reappropriated, an echo that connects with experiences of generations that she never knew. From Quim/Quima by Maria Aurèlia Capmany in the early seventies to more recent theatrical adaptations, it seems that there is always just a little more to be squeezed from Orlando, a new look at his life story. A hundred years after this novel was published, we recover the three film adaptations that have been made of it. In the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s, three filmmakers brought Orlando to the cinema; in each version, the character’s transgression takes its own unexpected forms.

Read more here.

Continue readingSALLY POTTER ATTENDS AN AUDIENCE WITH POPE LEO XIV

Pope Leo XIV came to become head of the Catholic Church by way of Chicago. You’d expect him to be well versed in the ’85 Bears’ 4-6 defense or the triangle offense of Michael Jordan’s Bulls. But algorithms? Who knew he might have such an understanding of the higher artistic aspirations of cinema? Today, the Pope held court at the Vatican with an audience of filmmakers, actors and executives, offering calming and encouraging words about the importance of movies and even the challenges facing the business right now.

Here is his speech, delivered to an audience that included Viggo Mortensen, Cate Blanchett, Greta Gerwig, Julie Taymor & Elliot Goldenthal, Azazel Jacobs, David Lowery, Monica Bellucci, Marco Bellocchio, Alba Rohrwacher, Darren Aronofsky, Spike Lee & Tonya Lewis Lee, Judd Apatow & Leslie Mann, Chris Pine, Sally Potter, Dave Franco & Alison Brie, Adam Scott, Gus Van Sant, Kenneth Lonergan & J. Smith Cameron, Joanna Hogg, Gaspar Noe, Albert Serra and Bertrand Bonello.

Read more here.

Continue readingSALLY POTTER'S RETROSPECTIVE AT BRITISH FILM FESTIVAL IN POZNAN

"This year's director retrospective is dedicated to Sally Potter, an artist who constantly redefines the meaning of auteur cinema and sets new boundaries for creative freedom,” says Dorota Reksińska, programmer of the British Film Festival and manager of Kino Muza in Poznań. Her unique style and cinematic language are tools she uses to reflect on the meaning of time, sexuality, feminism, and the search for human identity. For the first time in Poland, we are presenting a complete retrospective of the director's work, including the cult film ORLANDO starring Tilda Swinton, followed by a meeting with the director.

Sally Potter will meet with viewers several times during Q&A sessions after the screenings of her films, some of which will be shown in Poland for the first time. She will also take part in an industry meeting with representatives of the Polish film community. A real surprise will be the opportunity to meet the artist during a joint listening session of ANATOMY, the second solo album by Sally Potter, who is also a composer and singer.

Read more here.

SALLY POTTER ON BBC RADIO 3 ULTIMATE CALM WITH ERLAND COOPER

We are transported to the musical safe haven of the award-winning film director and musician Sally Potter. She shares a special piece of music that flows like water or breath, that always induces calm melancholy in her.

Listen here.

Sally Potter on BBC Radio 4

Sally Potter speaks with Fiona Shaw to celebrate 100 years of Virginia Woolf's novel Mrs Dalloway, exploring the revolutionary way she portrayed interior lives.

EPISODE 1: INNER LIVES

Three transformations of Virgina Woolf.

'Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself.'

A century on from the publication of Mrs Dalloway, Fiona Shaw explores what Virginia Woolf has to say to us today. With Clarissa Dalloway as our guide, we discover how Woolf captured and critiqued a modern world that was transforming around her, treated mental health as a human experience rather than a medical condition, and challenged gender norms in ways that seem light years ahead of even our present day discourse.

In this episode, Fiona Shaw speaks with authors, academics and artists inspired by Virginia Woolf, about how Woolf foregrounded interior lives.

Fiona hears from authors Michael Cunningham, Mark Haddon and Naomi Alderman; Woolf biographer Alexandra Harris; filmmaker Sally Potter; Professor of Modernist Literature, Bryony Randall; Professor of English, Mark Hussey; and Professor of Twentieth Century Literature, Anna Snaith.

Continue readingSALLY POTTER IN CONVERSATION AT ROUGH TRADE WEST

Rough Trade West is very excited to present an in-store In Conversation with film-maker and singer/songwriter Sally Potter and her long-time collaborator guitarist Fred Frith. Hosted by Scottish composer and producer Erland Cooper. The conversation will be followed by a signing from Sally Potter. This unique event celebrates the release of Potter’s second album 'Anatomy' via Bella Union.

Read more here.

Continue readingSALLY POTTER'S ANATOMY IN THE YORKSHIRE POST

Sally Potter 'songs are not good lectures'

One of British arthouse cinema’s most fêted directors and screenwriters, Sally Potter has also long had an interest in music. From her 1992 adaptation of Virgina Woolf’s Orlando onwards, her compositions have featured on the soundtracks to her films, and in 2023 she released her debut album, Pink Bikini.

Now comes a follow-up, Anatomy, comprised of a dozen self penned songs.

Read here.

Continue readingANATOMY LIVE AT CAFE OTO WITH SALLY POTTER & FRIENDS

To mark the release of film-maker and singer/songwriter Sally Potter‘s new album ANATOMY, coproduced with Marta Salogni and released by Bella Union, Café Oto is proud to host the only UK concert featuring Fred Frith (guitars), Alcyona Mick (piano), Aimée Farrell-Courtney (bodhrán), Ben Reed (bass) and Misha Mullov-Abbado (double bass).

Sally Potter has been exploring themes of human connectedness, morality, and mortality in a career that has spanned four decades, encompassing works as varied as the speculative historical epic “Orlando” and the acerbically witty comedy-drama “The Party”. In addition to her film work, Sally is a musician and singer-songwriter, a parallel vocation that began with improvised performances and concerts in the 1970s and 1980s and continued through composing music for the soundtracks of her critically lauded films. Her second album, ANATOMY is an entirely new affair for the multi-disciplinary artist—an eclectic and boldly visionary collection of songs that seek to tackle our species’ symbiotic relationship with the Earth, all while reflecting on the emotional threads that intertwine us all as people who share this planet.

Read more here.

Continue readingSALLY POTTER ON NTS RADIO

Listen to Sally Potter's NTS Radio session on the theme of longing here.

Continue readingSALLY POTTER'S ANATOMY IN THE TIMES

The film-maker Sally Potter talks to Ed Potton about writing zingers for her new album, working with Tilda Swinton and avoiding the bailiffs.

Read here.

Continue readingSally Potter at The London Review Bookshop with Iona Heath on John Berger

Iona Heath, author of new book Ways of Learning, & filmmaker Sally Potter on the late great John Berger on the 10th September

Continue readingSally Potter in PAPER magazine

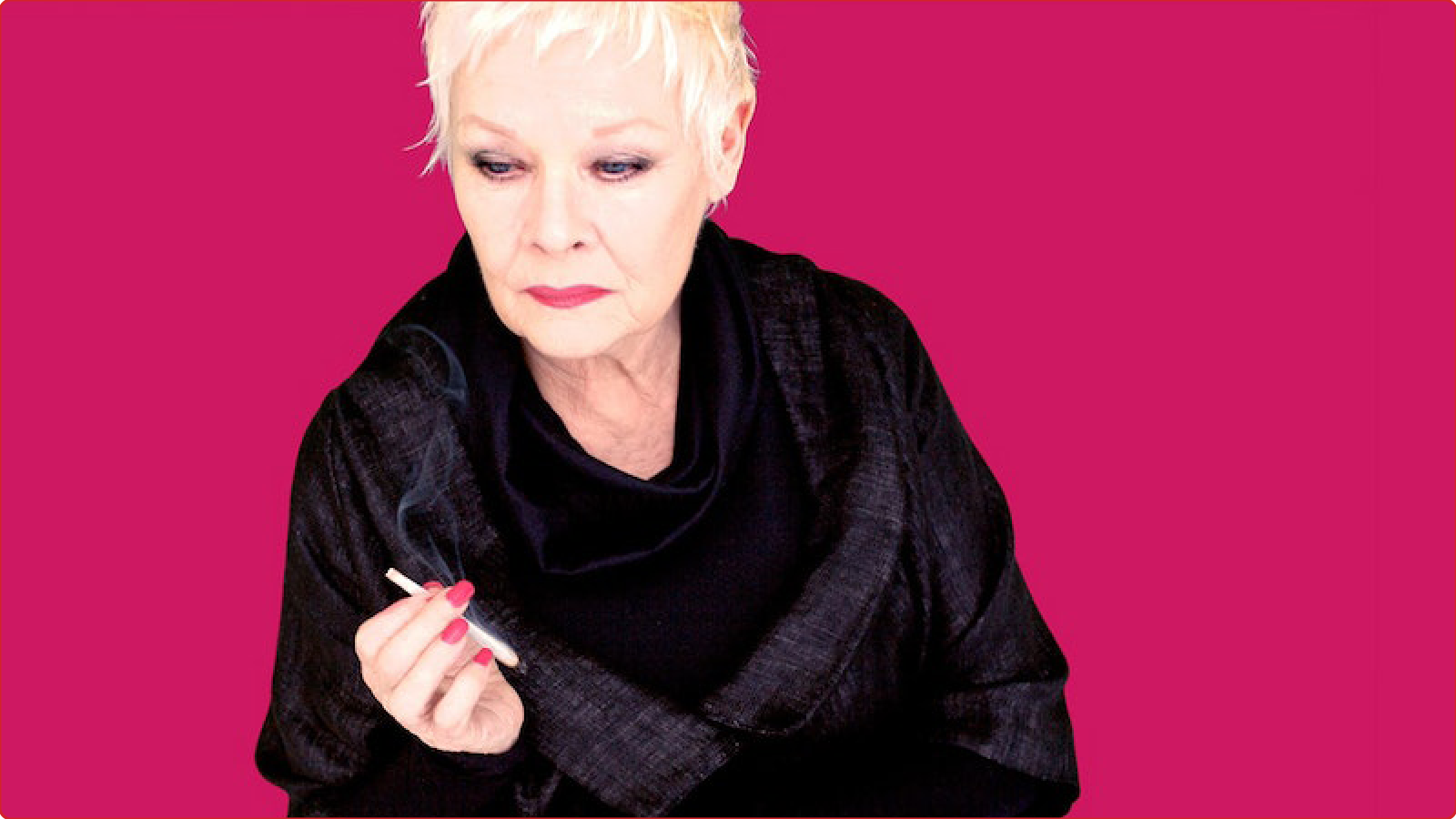

“Smartphone cinema” could sound to one like an oxymoron, but Sally Potter, the British filmmaker behind such essential works as Orlando, Gingerand Rosa and The Party, does not see the utility in such distinctions. There must be some way, she believes, to merge the syntax of cinema with the ubiquity of the mobile phone.

In 2024, this idea still strikes as provocative, so one can only imagine, though, how such a project would incite cinephile audiences in 2009, just two years after the release of the first iPhone. In Rage, Potter’s 2009 film, the director boldly explored such a question. The first film designed to be watched on a mobile phone (but also able to to be seen on the wide screen), Rage provoked a small moral panic when it premiered in 2009 at the Berlin Film Festival. “The film was treated as a news item rather than an artistic review,” Potter remembers. “There was one headline that said, ‘Sally Potter wants to kill cinema.’ And I thought, ‘This is the great passion of my life!’”

They were provoked, perhaps, by the formal challenge of this film (as being “for” the mobile phone), but also by the experimental format of the film’s narrative: a series of close-up monologues set against bright, single-color backdrops. Via these monologues, the story unfurls over the course of several days at a fashion show, where chaos, and eventually, murder, push the characters to test the limits of their own morality, hubris, greed and paranoia.

“To give narrative information by withholding all imagery, to see nothing except these faces coming and talking against a color: it's almost like a provocation,” says Potter. But it also fits neatly into the narrative framing. The film is conceived to be shot by a young child named Michaelangelo, who, mobile phone in hand (it was actually shot on a handheld camera), interviews the fashion show’s participants with a child’s blind curiosity.

The cast is stellar, and even a bit prophetic regarding the future of Hollywood: it includes the already iconic likes of Judi Dench, Jude Law, Steve Buscemi and Dianne Wiest, along with then-newcomers like David Oyelowo, Riz Ahmed and a pre-Suits Patrick J. Adams. Such a cast, and the truly gripping narrative, should have made Rage a crowd-pleaser, despite its fairly avant-garde format. But, it seems, the film’s essential provocation, and the monologue format, which is ubiquitous today in our age of TikToks and vloggers, was too ahead of its time.

Thankfully, Potter and company recognized that. After seeing the film in New York’s Metrograph theater during a 2023 Potter retrospective, the director decided to give the film another-go, this time on Instagram on TikTok. Breaking down the film into bite-sized Reels and TikToks, Rage is now available to view either piecemeal or in total through its own Instagram page and TikTok account. The question remains, though: is there a life for cinema on the smartphone? Today, due to the device’s overwhelming ubiquity, we are in a much better place to answer such a question.

PAPER chatted with Potter, while she was in the throes of the film’s Instagram premiere, about the film’s initial controversy, facing the chaos of the algorithm, smartphone cinema and unfolding gender roles in film.

Read here

Continue readingSally Potter's RAGE screening and instagram live Q+A at the Rio Cinema

Sally Potter will be at The Rio Cinema, Thursday 29th February for an exclusive screening of RAGE and in person Q&A with cast members Lily Cole and Jakub Cedergren joining on Instagram live.

Read here

Continue readingSally Potter to re-release 2009 feature 'Rage' on Instagram announced by Deadline

British filmmaker Sally Potter has set plans to re-release her 2009 feature Rage, starring Riz Ahmed, Lily Cole, Jude Law, and Judi Dench, as a series of posts on Instagram, to mark the film’s 15th anniversary.

Potter has said the movie will unravel over several “real-time” posts across seven days, starting February 23.

The film also stars Patrick J Adams, Jacob Cedergren, John Leguizamo, Eddie Izzard, David Oyelowo, Dianne Wiest, Steve Buscemi, Adriana Barraza, Simon Abkarian and Bob Balaban. The original concept in 2009 was for the film to be watched on smartphones. The synopsis reads: Michelangelo, an unseen schoolboy armed only with a mobile phone, goes behind the scenes at a New York fashion show for seven days in which an accident on the catwalk turns into a murder investigation, and his interviews with key players become a bitterly funny expose of an industry in crisis.

The story unfolds shot by shot, over the week in which Michelangelo shoots and posts his interviews. The film was shot as a series of to-camera monologues. These will be released in sequence across the 7 days, with each shot as a new Instagram post, posted throughout the day. The production believes this will be the first feature film released on Instagram.

“Rage is an exploration of the burgeoning power of social media and the generational divide between those born into a digital world and fluent with its rapidly evolving forms, and those for whom it remains a dark, opaque art,” Potter said.

“The setting – the competitive, narcissistic, and economically unstable world of fashion with its hangers-on, critics, models, dressers, seamstresses, and publicists – is an atmosphere made chaotic by the feeding frenzy of celebrity. But it is also a world in which, despite appearances to the contrary, each individual grapples with insecurity and private terror.”

On Thursday, February 29, when the Instagram release is completed, there will be a Q&A with Sally Potter and the cast streamed live on Instagram from the Rio Cinema in Hackney. Rage is written and directed by Sally Potter and produced by Christopher Sheppard and Andrew Fierberg for Adventure Pictures.

Read here

Sally Potter’s ‘Rage’ Instagram re-release exclusive by Indiewire

Sally Potter is taking her “Rage” to Instagram. IndieWire can exclusively reveal that the lauded British filmmaker will release her iconic 2009 film in a series of Instagram posts beginning on February 23.

“Rage” was the first full-length feature film specifically designed to be watched on mobile phones. Shot in a vertical format as a series of to-camera monologues, the Instagram release will feature a new shot being posted daily, leading up to the March 8 theatrical release from Abramorama to mark the 15th anniversary of the film’s Berlinale debut. “Rage” will screen with anniversary theatrical and non-theatrical engagements across North America and land on a Direct-to-Consumer digital and VOD placements later.

The film first premiered at the 2009 Berlin Film Festival, and follows an unseen student named Michelangelo who goes behind the scenes at a New York fashion show. However, over the course of a week, Michelangelo is thrust into the center of a murder investigation as he interviews possible witnesses to the crime.

The Instagram rollout mimics the movie’s protagonist Michelangelo’s own voyage onscreen. The film was originally released on mobile applications via Babelgum in 2009 before having a theatrical run.

“Rage” stars Jude Law as a female model named Minx, Judi Dench as a fashion critic, and real-life model Lily Cole as a fictional catwalker named Lettuce Leaf. The ensemble cast is rounded out by Riz Ahmed, Eddie Izzard, John Leguizamo, Steve Buscemi, Bob Balaban, David Oyelowo, Dianne Wiest, Patrick J. Adams, Simon Abkarian, Adriana Barraza, and Jakob Cedergren.

“‘Rage’ is an exploration of the burgeoning power of social media and the generational divide between those born into a digital world and fluent with its rapidly evolving forms, and those for whom it remains a dark, opaque art,” Potter said in an official statement. “The setting — the competitive, narcissistic, and economically unstable world of fashion with its hangers on, critics, models, dressers, seamstresses, and publicists — is an atmosphere made chaotic by the feeding frenzy of celebrity. But it is also a world in which, despite appearances to the contrary, each individual grapples with insecurity and private terror. When this world of glittering surfaces becomes enmeshed with violence and death, it is Michelangelo who sees, hears, and records the unfolding events for posterity posting his images into a hungry world.”

Producers Christopher Sheppard and Andrew Fierberg added, “Instagram since its launch in 2010 has become an inventory of mass self-portraiture. ‘Rage’ takes this a step further, exploring with each portrait-like post how storytelling itself has shifted in the age of social media. We are all excited to see it presented to audiences exactly as Sally first imagined it, short form social media posts directly from Michelangelo to the world.”

On February 29, after the Instagram release is completed, Potter and the cast will livestream a Q&A panel from the Rio Cinema in Hackney, London. Letterboxd‘s Ella Kemp will moderate the discussion, which will exclusively debut on Instagram.

The 2024 multi-modal release strategy for “Rage” was created in association with Theorem Media, a U.S.-based non-profit organization “that empowers all forms of storytelling aimed at inspiring critical thinking, media literacy, and a more educated and civically engaged society.” Adventure Pictures, Studio Fierberg, and Abramorama co-shared the announcement.

Abramorama CEO Karol Martesko-Fenster and Theorem Media CEO Douglas Dicconson added, “We are so grateful to coordinate this innovative release team including all of us across both Theorem Media and Abramorama, as well as everyone at Adventure Pictures, Tarbert Digital, and GATHR, coming together to bring Sally’s visionary form of storytelling forward as it was intended. It has been so fascinating to see the entire media landscape take form around a story, as predicted by that story, over a 15-year period. It seems that technology has finally caught up to Sally.”

As Oscar-nominated “Orlando” and “Rage” writer-director Potter told The New York Times in 2009 in a prophetic statement, “We are culturally saturated with fashion. We are visually inundated with it. It’s so visible now, so dense in our imagination. … Whatever one shows, by the time the film comes out, is out of date.” Potter also helmed eight other features across her career thus far.

The Instagram premiere of “Rage” follows the marketing trend that Paramount and Warner Bros. recently used with the respective releases of “Mean Girls” and “The Sopranos” on TikTok to celebrate anniversaries.

Check out the anniversary trailer for “Rage” below, plus an IndieWire-exclusive clip.

Read here

Continue readingSally Potter talks at the BFI about the lasting impact of The Red Shoes

We are delighted to announce that filmmaker Sally Potter, dance writer and critic Judith Mackrell as well as independent curator Helen Persson will join the panel discussion hosted by Pamela Hutchinson, author of The Red Shoes (BFI Film Classics).

Join us to dive deeper into the breathtaking world of Powell and Pressburger’s Technicolor masterpiece. Pamela Hutchinson, author of the recently published BFI Film Classics book on The Red Shoes, will present an illustrated talk examining some of the elements that make the film so endlessly fascinating. She will then be joined by special guests to consider the film’s wide-reaching influence on cinema and other artistic forms.

Read here

Continue readingSally Potter at the Cambridge Film Festival

Orlando, this luscious classic turns 30 this year and it is more resplendent than ever. Tilda Swinton takes us on a journey through Elizabethan England, in time, through gender, starting as the young Nobleman Orlando to then one morning wake up a woman. Sally Potter bases her most acclaimed film on Virginia Woolf’s eponymous novel and the final product dazzles with its affective visual style and simmering meditation on death. Lady or Gentleman, Orlando remains a queer staple that will bring literary lovers, Swinton stans, and cinephiles together around the fire. A spectacle, a joy, a profound piece of cine-philosophy.

Sally Potter also considered Michael Powell a dear friend. She has shared how Powell and Pressburger’s work has influenced and reflected her own perspectives on identity and history and wrote a dedication to Michael at the end of Orlando.

We are thrilled to welcome director Sally Potter for a Q&A with the audience after the film.

Unfortunately, due to a technical issue, the film will no longer be shown with English subtitles, but there will still be BSL interpretation provided for the film introduction and the post-screening Q&A

Sally Potter on BBC Radio 4's This Cultural Life

Film-maker Sally Potter talks to John Wilson about the formative influences and experiences that inspired her own creative work.

Continue readingSally Potter on Caropopcast

You may know Sally Potter as the groundbreaking English director of such films as Orlando, The Tango Lesson and Yes, but now she also is a recording artist. At age 73 Potter has released her first solo album, Pink Bikini, writing, singing and playing keyboards. The songs look back on her teenage years in 1960s London, when she was discovering her own sexuality, wrestling with shame, rebelling against her mother and finding her artistic and political voices. Speaking from her studio, Potter also reflects on the transformative effect of having a film camera in her hands at age 14, the paucity of female filmmakers when she started and her unwillingness to let age limit her creative pursuits. As she puts it: “Who cares about the calendar?”

Continue readingSally Potter in Interview magazine

Sally Potter in conversation with award winning violinist Viktoria Mullova for Interview Magazine.

Continue readingSally Potter in Document Journal

Sally Potter talks time travel and other mysteries

Continue readingSALLY POTTER ON Q WITH TOM POWER (CBC)

Filmmaker Sally Potter built her reputation as a highly respected auteur who launched Tilda Swinton’s career in the Oscar-nominated film “Orlando.” Now in her 70’s, she’s kickstarting a music career with her debut record, “Pink Bikini.”

Continue readingSALLY POTTER IN THE DAILY CALIFORNIAN

Sally Potter ruminates on adolescent rage, longing behind debut album 'Pink Bikini'

JULY 16, 2023

On the cover artwork of his seminal 1963 album The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, Dylan languidly hunches over, sporting a slight smile. He’s accessorized by an unnamed woman clasping his arm — her overflowing, dizzy sentiment evoking enough feeling for the two of them, even as his imagination is, of course, the guiding force behind the record.

“It was puzzling that, on the cover of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, there’s Bob Dylan slouching in the snow arm and arm with this person. She’s of equal size, equal weight in the image, but isn’t quite named anywhere. We don’t know who she is. So there’s this funny mixture of being present but being invisible,” Sally Potter mused in an interview with The Daily Californian. “What did she do? Did she sing? Did she write lyrics?”

It was this very yearning to know the faceless woman — a woman that, in essence, was an amalgamation of her mother, her grandmother and the sublimated desires of generations of women — that stirred Potter as a budding artist then and now, informing the temper and tenderness of her debut album Pink Bikini, which releases Friday. One particular track on her debut album, “Black Mascara,” notably references “fighting with my mum,” haunting her and not being able to bear to see her for long.

“The feeling I got above all from (my mother), and to some extent from my grandmother as well — who also studied singing and was an actress in her twenties — was disappointment,” Potter said. “Disappointment about what they weren’t able to do … with limits that life seemed to have placed on them. … Both my mother and my grandmother didn’t dramatize it all the time. But I felt it so strongly. I felt the grief for what they weren’t able to do with their lives. Why did they accept these limited lives? I wanted them to fight back. Later I realized they couldn’t.”

Grief bubbled into rage, and rage into perhaps an insatiable desire for authorship amid these very constructs and institutions that had long barred women from entry. Indeed, the album sees Potter traffic in a modus operandi entrenched in a longing to transcend a psychosomatic, intergenerational malaise.

Over the past few decades, Potter has found success in filmmaking, a standout of her directorial oeuvre being the 1992 Virginia Woolf adaptation “Orlando.” In “Orlando,” Potter wielded an unabashedly postmodern lens, conversing with Woolf’s text through a lush, formal subjectivity that brandished a score of anachronistic synths and constructed a narrative concerned with leitmotifs rather than continuity.

Potter’s work in music, though, is not a new endeavor for the artist, having toured with the avant-garde band the Feminist Improvising Group in the 1970s — and having produced some of the music for “Orlando.” It is perhaps a more acute cut to her artistic roots, with music being an intergenerational mainstay: Potter’s mother was a music teacher and her grandmother an actress and singer.

“I never really left music,” Potter said. “One of the feelings that stayed with me (from touring) was the feeling of a live audience. You begin to sort of feel through them what works, what’s getting across and what’s not getting across. That feeling of audience that you’re working for becomes internalized after a while. It’s very useful as a filmmaker too — to be able to feel the audience even when they’re not there, even when you’re working in solitude for a very long time and imagining them watching it in the future.”

In her return to “a world of pure sound,” there came “a pleasure of deep listening” that comes through what Potter deems an art form that evinces what is “beyond representation.”

“Film is always representational. The way that the eyes take in information — every frame of a film is jam-packed with thousands of pixels and bits of information that people can absorb,” Potter said. “But music evokes a kind of universal feeling, transcendent feelings. It’s a shorter form. Each time it can take one into this whole other zone through the ears in which you link with your own deepest feelings, but you don’t necessarily have to represent those feelings in a concrete form.”

Through a single, succinct title, Potter employs the short form of song to sublime, meticulous ends. The title of Potter’s debut, which is also a track on the album, is one that encompasses an amusing, melancholy anecdote, demonstrating the paradoxical feelings of adolescence and the gradual, liminal descent into womanhood.

“Just the phrase ‘pink bikini’ makes me laugh. It’s ludicrous,” Potter said. “I really did see a pink bikini in this shop window and I thought, ‘if I get that bikini, my life would be different. I’ll be attractive. I’ll look good on the beach.’ So all of my longing got focused on this bloody pink bikini. So, for me, it’s a sad thing as well, about teenage longing — particularly for someone growing up as a young girl — and about all that focus on your body, on your clothes and that idea that if you have just that one thing, it’ll make the difference.”

The thematic ambitions of Pink Bikini recall the artist’s perhaps most directly self-reflexive film “Ginger & Rosa,” a coming-of-age picture centered on a young girl growing up in 1960s London; her fraught relationship with her housewife mother and intellectual father; and her trajectory toward activism and rebellion. Just as Potter toed implicit and explicit barriers then, she finds herself doing so through the release of Pink Bikini, even as she returns to recurrent themes and feelings in her body of work.

“I was the first female director in the UK since the Second World War,” Potter said. “It was ridiculous when I started — I really was one of the few female filmmakers and that’s very different now. Now, I find myself in this strange position at an older age of putting out a debut album. I’m going against the grain if you like, and trying to just follow the longing and the certainty of what I feel needs to be expressed in some way. Not necessarily for my benefit — hopefully for my benefit — but also mainly because I hope that this is something that there is a place for in the world and in the culture.

Continue readingSALLY POTTER ON MEET OUR MAKERS PODCAST

In this chat, we get to meet the fantastic, storied filmmaker Sally Potter. The writer-director of such acclaimed and varied films such as Orlando and Ginger & Rosa, Sally is actually just now releasing her debut full-length album (!) which is called Pink Bikini. In this conversation, Sally and I talk a lot about the new record - its themes, its songs, its lyrics, its music, some of her influences and inspirations - as well as what drove her to recording and releasing such a personal singer-songwriter album now, after such a robust career in cinema. We talk about her film work (especially the Tilda Swinton-starring, Virginia Woolf adaptation Orlando), how her filmmaking overlaps with her music making, and so much more. It was a humbling honor to talk to a cinema great, and her new album is such a delightfully wondrous surprise. I think you'll enjoy this as much as I did. Thank you for listening.

Listen here on Meet Our Makers

Continue readingSALLY POTTER IN ASSOCIATED PRESS

LOS ANGELES — Award-winning director Sally Potter has challenged British society throughout her 50-year career, in films like “Orlando,” “The Party,” and “Ginger and Rosa.” Now, at 73, Potter’s creative resolve forges on with her first studio album, “Pink Bikini.”

The LP, self-released Friday, is a semi-autobiographical collection of alternative tracks that detail Potter’s adolescence in 1960s London.

Across 12 songs, the filmmaker revisits tumultuous relationships and oppressive social strictures.

“There’s something very life-affirming about working in another medium, learning a new skill or making a change at what was considered to be a point in one’s life where you’re supposed to know exactly who you are and what you’re going to do,” Potter told The Associated Press.

Potter found lyrical inspiration in notebooks she filled with poems over her lifetime. Coincidentally, the songs on “Pink Bikini” deal with a variety of different subjects, including frustration with beauty standards (“Ginger Curls”), a “ban the bomb” march (“Black and White Badge”), and female authorship (“Ghosts”), delivered atop minor keys and alluring instrumentals.

“Some people say I have a rhyming gene,” Potter says.

The AP spoke to Potter about making the move from movies to music. Answers are edited for clarity and brevity.

AP: Your background is interdisciplinary; you’ve co-composed or curated music in your films. But when did this album begin for you?

POTTER: It’s quite a mystery to me, actually. Why now? Why this? I think I felt a very strong desire to work with the apparent simplicity of the song form. After making big films that always involve vast numbers of people and a lot of money ... the appeal of the short form is so enduring and so emotionally rich and so direct and so intimate.

AP: What was it like revisiting your adolescence on this album, at this stage in your life?

POTTER: I’m not sure she’s ever left me, actually. I’m not sure that any of our young selves ever leave us. But revisiting those memories is such a strange thing, and that’s one of the things that the songs (are) about: Am I remembering this? Or am I remembering a photograph of this? And then in the act of telling the story, because each of the songs is a small story, one begins to kind of rewrite history.

AP: How do gender dynamics influence your songs?

POTTER: I chose these teenage years because (it is) the moment of intense crisis around gender identification, when you first start noticing that you’re being treated according to the sex you were born. If I just speak about myself, and my generation of girls, as we were moving into puberty as a time of great loss, loss of freedom, dynamism ... all of a sudden (you’re) having to think what impression you’re making and the restrictions of being a female. At the same time, it’s an incredible kind of growth, seething with hormones, feelings, confusion, trauma, intensity, and finding out very many things about yourself in the world. It’s a very brilliant, intense period to write about.

AP: On “Pink Bikini,” are you exploring what it means to be like a woman reclaiming artistry?

POTTER: I would say not so much reclaiming as carrying on regardless of whether people want to or not.

AP: Songs like “Ginger Curls,” “Pink Bikini” and “Hymn” are intertwined with a feeling of shame. Does shame intersect with your sense of femininity?

POTTER: I think young girls learn to feel shame. (Even) before social media, we had a very problematic relationship with the body, where it’s a double message. You’re supposed to display (yourself) on the one hand, and be proud of it, on the other hand, you’re supposed to hide it. Because if you display it too much, you’re a slut. And if you hide it too much, you’re frigid. That was very much a kind of sixties and seventies thing — those impossible, contradictory demands of all women.

“Hymn” is a fight back against religious oppression. It’s a fight back against shame. A show of love between people of the same sex. That was more the feeling of all of the songs actually, about this oppression that suddenly arrives.

AP: You bring up nuclear warfare in “Black and White Badge.” Your films also talk about this period and political dissidence. How was it exploring your life and those feelings in music compared to in film?

POTTER: In film, you can tell the story in a more rounded way through characters, put words in people’s mouths, set up the situation, and get lots of visuals. In a song, it’s evocative in a distilled way, an era with simple language. I thought, “How can I write about something that was so important to me — climate change, the threat of an apocalypse essentially — and not to make it too heavy?” I wanted to lighten it. I sang in a fairly undramatized way. You can be a 12-year-old girl on a march — militant against the very existence of nuclear weapons on the one hand — and on the other hand, worry about not being looking cool enough. There’s a bit of humor in the midst of fear of the apocalypse, the ultimate terror.

AP: Are there questions from your ‘60s childhood that you think are relevant in 2023?

POTTER: One can’t mention climate change too many times because I think the fear of everything ending — what’s bigger than that? There is nothing bigger than that. It’s paralyzing.

The Cuban Missile Crisis, which (happened) when I was 11, looked very close to being World War III. I think (this generation’s) feeling of crisis is similar to then. Confusions around sexuality ... and domestic life. There are so many things in common, and those are the simple things.

Continue readingSally Potter on BBC Radio 4s Front Row

Filmmaker Sally Potter on her first music album.

Continue readingSALLY POTTER IN THE FINANCIAL TIMES

Filmmaker Sally Potter on her first album: 'Part of me relishes being a renegade'.

Continue readingBLACK MASCARA MUSIC VIDEO ANNOUNCED IN DEADLINE

Filmmaker Sally Potter Shares First Music Video From Her Debut Album 'Pink Bikini'.

EXCLUSIVE: Last month, we told you that British filmmaker Sally Potter (Orlando, The Party) has written and recorded her debut music album, Pink Bikini. Today, we can share the first video Potter shot for the project.

The video is for the single Black Mascara. It features Potter in a monochrome frame, turned away from the camera, and performing a hula hoop routine as the song unravels with lyrics popping up on the screen in bright red typeface. Oscar-nominated cinematographer Robbie Ryan (The Favourite) shot the project alongside a small crew of graduates from the UK’s National Film and Television School.

“Black Mascara was one of the earliest tracks I wrote for Pink Bikini, an album of songs based on a look back over my shoulder to the despairs and longings of my turbulent teenage years; a time of change: the end of childhood, the beginning of life as an adult,” Potter said.

“Making the video was a different kind of return. It needed to be made in the way I made films when I first started as a teenager. Back then I had no money, training, or equipment. The need to invent and imagine things out of nothing became part of a philosophy I later named ‘Barefoot Filmmaking’. It meant working with minimal means, borrowing gear, and working with the goodwill and energy of a few beloved friends and co-conspirators.”

Pink Bikini will be released on July 14. Billed as a “semi-autobiographical” collection of songs, the album will feature music and lyrics by Potter, and will be based on the filmmaker’s experience coming of age as a young woman in 1960s London, as a “young rebel” and activist. Musical arrangements on the album will feature work from guitarist Fred Frith, who has long collaborated with Potter on her film scores.

Best known for her directorial work on features such as 1992’s Orlando, an adaptation of Virginia Woolf’s classic novel starring Tilda Swinton, and Ginger & Rosa (2012), starring Elle Fanning, Potter had a music career that predates her work in cinema. During the 1970s, she was a member of the Feminist Improvising Group, an avant-garde band that toured extensively in Europe.

Potter also performed with the Film Music Orchestra and collaborated (as lyricist) with Lindsay Cooper on the album Oh Moscow, performing in the USSR and East Berlin in 1989, before the wall came down.

SALLY POTTER THE MUSIC OF CINEMA AT THE GARDEN CINEMA

The Garden Cinema is delighted to host a weekend of screenings and events celebrating the films and music of one of the UK’s foremost artists: Sally Potter. This retrospective anticipates the 14 July release of Sally’s debut album, Pink Bikini, a semi-autobiographical collection of songs about growing up female in London in the 1960s, as a young rebel and activist. Sally will be live at the Garden Cinema for Q&As following Orlando and Yes and giving a special introduction to The Party. Additionally, Sally will be discussing her album, film music, and more with Miranda Sawyer on Friday 9 June.

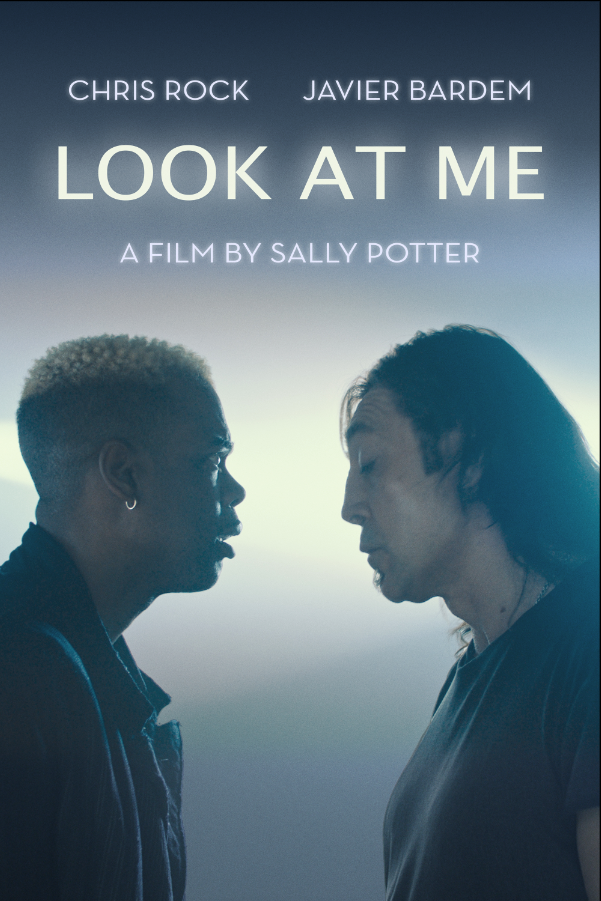

Continue readingLOOK AT ME showing at Clermont Film Festival

Look At Me

The British filmmaker Sally Potter’s audacious adaptation of Virginia Woolf’s classic novel Orlando, with Tilda Swinton, in 1992 initially brought her to the attention of wider film audiences. Other films followed, including The Tango Lesson (1997), The Man Who Cried (2000), Yes (2004), Rage (2009), Ginger & Rosa (2012), The Party (2017) and The Roads Not Taken (2020). Her films have won over forty international awards and have been nominated for the Oscars and BAFTAs. In 2012 she was made a Member of the Order of the British Empire.

In 2022, Potter made the short film Look At Me with Javier Bardem and Chris Rock, which will be shown during the Festival’s opening ceremony on Friday, 27th January in the Salle Cocteau. Audiences on hand will then have the opportunity to dive deeper into her world by talking directly with her, in French in public, with the MC Abla Kandalaft, a journalist for the Brasserie du Court (the Festival blog).

Read the piece here: https://clermont-filmfest.org/..

Continue readingSally Potter and Javier Bardem video Q&A

Shorts Exclusive: Sally Potter Talks to Javier Bardem About Their Collaboration on ‘Look At Me’

Why is it so hard for men to talk about their feelings? In Sally Potter’s hypnotic short film, Look At Me, two men (played by Javier Bardem and Chris Rock) face off in a surprisingly emotional showdown to see who will break first. It has qualified for the Live Action Short Film Oscar.

In an Awards Daily exclusive, Potter sits down with Bardem to talk about their second collaboration (they worked together for The Roads Not Taken), and it’s a warm feeling when they see each other on the opposite sides of the Zoom screen. They talk about power struggles and how Chris Rock really gave himself over to the safety of the material, Potter comments on going back to short form filmmaking. It is an invigorating conversation between two dedicated artists.

Read full piece and watch Q&A here: https://www.awardsdaily.com/20...

Continue readingSally Potter Confronts Male Anger In Oscar-Qualifying Short ‘Look At Me’

A boundary between helping a loved one and walking away from them is being played with in Sally Potter’s thought-provoking and sly short film, Look At Me. It explores masculinity and anger as we witness creative differences spiral into something more personal. Anchored by a pair of duelling and dancing performances from Javier Bardem and Chris Rock, Look At Me makes us wonder what all men are hiding behind their outbursts and swagger.

A refined and illustrious evening is being planned to encourage guests to open up their pocket books for a worthy cause, but the entertainment still needs fine tuning. Potter’s film opens on a rehearsal where Bardem’s Leo, a rock drummer whose most successful days are behind him, is butting with the gala organizer (Rock) as they try to unify their vision. His beats are loud and rough, and Savion Glover’s tap dancing is being overshadowed by Leo’s raucousness.

Rock’s character begins to strip down Leo’s equipment, and the drummer begins to feel alienated. His art is quite literally being taken away from him piece by piece. But then Potter’s film takes a gentle and unexpected turn as we learn about the connection between these men and just how exhausted the organizer is. While you could be fed up with Leo’s behavior, Bardem brings a weighted sadness to the part. When we see him alone, his eyes are cast downward or even inward as if he is replaying painful memories over and over again in his head.

Rock has slowly been adding more dramatic roles to his resume (Fargo and even Spiral), and here he gives his most mournful performance. He is a man fed up with Leo’s behavior but he cannot fully release himself. Rock is fantastic.

Men push and shove and explode to show their feelings. It’s stupidly primitive, and some cannot find eloquent words to express themselves. Potter sets the stage for these men to explode with their fists and their words, and it’s contemplative, measured, and meaty.

read full piece here: https://www.awardsdaily.com/20...

Continue readingLook At Me reviewed by FilmThreat

A clash occurs between a former drug addict and the one who stood by his side during the worst of it in Sally Potter’s short film, Look at Me.

During the rehearsal for a big gala event, a drummer (Javier Bardem) and a dancer (Savion Glover) duet together in a battle between the beat of the drum and tap in this artistic performance piece. The gala director stages the two “combatants” side-by-side in separate chain-link cages. The star of this piece is the dancer, but the jealous drummer refuses to play backup, forcing himself into a battle of wills with the director.

As the frustrated drummer storms off, the director chases after him. We soon find that the two are lovers, and the drummer has struggled with drug addiction (on and off again) for quite some time. The director was always there to bail him out, but not this time.

Look at Me uses the intense rhythm of the drum and tap to illustrate the struggle those with addictions face between relapse and sobriety. The story sets this inner conflict against a real-world one, the one between the person who has stood by them, only to see the cycle of addiction loop around once again. Writer/director Sally Potter masterfully blends the elements of rhythm and brilliant acting from Rock and Bardem to complement the heartbreaking story of addiction.

read piece here: https://filmthreat.com/reviews...

Continue readingLook at me is a is a "stunning examination of the pressures of work, and providing for others"

Hollywood has an obsession with ‘what could have been’. It’s a question which haunts many of its finest films, from ‘La La Land’ to ‘Sunset Boulevard'. However, it is perhaps ‘A Star Is Born’ - that eternal Hollywood fairytale - to which ‘Look at Me’ is most similar. Similar, but also distinctly its own short, ‘Look at Me’ takes the best parts of Hollywood classics, but is also inventive, and creates its own story.

Directed by Sally Potter, whose previous credits include ‘Orlando’ and ‘Ginger and Rosa’, ‘Look at Me’ is a stunning examination of the pressures of work, and providing for others. Potter imbues each scene with a sense of emptiness - from a sparsely populated warehouse to an expansive rooftop - illustrating the isolation felt by Leo (Javier Bardem reprising his role in the underrated 2020 film ‘The Roads Not Taken’) and his boss, and partner, who is played by Chris Rock.

Leo is a drummer, that much would be clear just from his long, grungy hair, although the fact that he’s sat behind the drums is perhaps a better indicator. He’s been hired by Rock to play the beat for a dancer at a fundraising gala for the unjustly incarcerated. In what appears to be a cage, Leo plays his drums, with intrinsic close-ups of his face, as Rock watches on disapprovingly, eventually pulling the rehearsal to a stop with the belief that ‘simpler would be better.’

So it goes on, and Rock continues stripping away parts of Leo’s drum kit and in turn the creativity from his performance. Understandably, tensions rise, as Leo sees a man with no understanding of his art, stripping away any creativity in order to produce a monotone, corporate sound. As tempers flare we come to understand the complexities of their relationship - partners both publicly and privately - and the performance becomes a battleground for their relationship.

Basked in fluorescent lights, Potter masterfully sets up the dynamic between the two, and creates an ethereal, yet nonetheless grounded, setting of glorious blues, reds and greens. Working with cinematographer Robbie Ryan (Oscar-nominated for ‘The Favourite’) the short looks more beautiful than most feature films. The gala itself is lit by glowing candles, with an almost medieval sense further illustrating the conflict within their relationship.

Bardem and Rock give nuanced performances and have chemistry which softens the rougher aspects of Potter’s script, which sometimes lacks guile or subtlety in its message. Bardem is quite restrained, with blunt line delivery and hopeless eyes, he perfectly paints the picture of a man jaded from both his love and passion. Rock gives a performance which reminds you of how versatile an actor he is, as adept at drama as at comedy, and able to carry an otherwise lacking screenplay.

Though its message is at times a little too on the nose - satirising rich liberals, who mean well but often fail to see their own hypocrisy - ‘Look At Me’ is a reminder of Sally Potter’s immense talents, which have long been undervalued in Hollywood, and her wonderful storytelling ability, whilst giving Javier Bardem and Chris Rock the chance to shine once again.

read piece here: https://www.ukfilmreview.co.uk...

Continue reading

Metrograph interviews Sally Potter on her body of work

Best known for her 1992 adaptation of Orlando, Sally Potter is among the few artistic polymaths who’ve left their mark on narrative feature film. As a teenager in England, Potter started experimenting with an 8mm camera her uncle had loaned her, and began studying choreography and performance soon after that, co-founding a highly influential dance group (Limited Dance Company), before creating series of expanded cinema pieces, such as Combines (1972), a multiscreen film/dance work with choreographer Richard Alston and the London Contemporary Theatre. Her incisive but never didactic worldview has allowed her to explore issues of class, gender, race, climate, and colonization, as well as the act of artistic creation. I spoke with Potter in early September at her London studio, via Zoom, about her relentlessly experimental, ahead-of-its-time filmography.

VIOLET LUCCA: This week has been marked by the deaths of Queen Elizabeth II and Jean-Luc Godard. Both of these very different personages seem relevant to your filmography—for example, Thriller (1979), The Gold Diggers (1983), Orlando (1992), and Rage (2009) are each explicitly confronting imperialism, gender, and pageantry. So what does the Queen’s death mean to you? Is it a sign of anything shifting, or everything just staying the same?

SALLY POTTER: It’s everything rising to the surface—the roots of the unconscious relationship with queendom, which is sort of mythological. I dreamt of the Queen last night. And I thought, “Oh my God, she’s even inserted herself into my dream life!” Well, it’s not her who has inserted herself, it’s the power of mythology, which is as powerful as it ever was for the early Greeks. Here in the UK, it’s like an outbreak of madness—madness mixed with a sort of deep vein of emotion that is actually not about the personal at all, but about the sense of being alive or being dead. It’s like everyone has kind of gone mad for their own lost ancestry, or their own lost grandmother, or their lost country. Because, you know, whilst it looks as though most British people are in denial about the end of empire, in reality, everybody knows. So, that’s the Queen. But it’s a bigger subject than that, because it’s like, how can people still be talking about being reigned over? How is this language still possible? It is all quite extraordinary, and coming from sources that I would never have expected. There’s a few lone, timid voices of republicanism. But people basically want to be polite in what’s perceived as a time of what, for many people, feels like personal grieving, when in fact it’s something mythological that they’ve lost.

As for Godard, I adored early Godard. Like everybody else in the world of cinema, we’ve either been influenced consciously or unconsciously by his work. Although I have to say, just to remind everybody, Agnès Varda came first in many ways. Things that are credited to the guys were things she’d already developed in La Pointe Courte (1955). But he was there, being visible and authoritative in a way that he could be. He came from traditional criticism, so his work was all about cinema that was criticizing other cinema, as well as celebrating it. His death is not accompanied by pageantry. But on the other hand, the things he made live on. The royal family doesn’t make things, they inhabit roles.

VL: Yes, they make scandals. They make entertainment.

SP: And other people turn the things that they do into scandals, things that might otherwise go unnoticed. Because they lead symbolic lives, everything they do is symbolic or on a bigger scale.

VL: Right, but on the other hand, they own real land and get real public money, they have exemptions from real laws…

SP: They have always done. When we’re talking about the reign of Elizabeth II, we’re actually talking about the reign of Elizabeth I, which is where the British Empire started; the beginning of expansionism and the Empire was Queen Elizabeth I. I read in the paper this morning that the amount of wealth behind the royal family is in the billions. It’s extraordinary. Wealth and ownership and class—these are corrupt diseases.

The Gold Diggers (1983)

"MY LARGER STRUGGLE HAS ALWAYS BEEN HOW TO ACKNOWLEDGE THAT POLITICS IS EVERYWHERE, IS EMBODIED DEEPLY IN EVERYTHING—IN EVERY PIECE OF CLOTHING, EVERY SURFACE WE TOUCH, EVERY RELATIONSHIP WE HAVE, IF YOU OPEN YOUR EYES."

VL: I don’t mean to be reductive, but there’s a Marxist feminist critique that runs throughout your filmography—The Gold Diggers, Thriller, Rage, and so on. This sort of politics is experiencing a bit of a resurgence. Do you find that heartening?

SP: The people I’m close to now who are in their early twenties, by and large, I find very encouraging people to be around. They’re very aware, analytical, and activist—I know, this is crazy generalization, but they’re a fantastic generation. It’s hard to be encouraged in a much wider sense, partly because of the way information is disseminated, shrouded in the most utter gloom and despair. To find a contradictory sort of pathway through that, it’s tricky.

You’re right to say that my films come from this, in a way, activist impulse. But it’s always been an impulse that is in part political, part aesthetic. So Godard was important to me, as were so many other individual filmmakers, because of what they were doing with the form as much as any wider politics. My larger struggle has always been how to acknowledge that politics is everywhere, is embodied deeply in everything—in every piece of clothing, every surface we touch, every relationship we have, if you open your eyes. On the other hand, to work effectively in cinema, music, or the arts, you can’t take that political awareness and put it on the form. The form itself is embedded in politics, but also in its own aesthetic history, that is, to some extent, transcendent of politics. To find forms that evoke those deeper levels at the same time as encouraging a kind of analytical explosion, if you like, of given concepts about the world we live in—that’s what I’ve been wrestling with for a long time.

VL: I would love to talk about the role of pleasure in your films, which is on the terms of the female characters’ pleasure, but also formal pleasure, the pleasure for viewers: things like the sumptuous flashes of the fashion world in The Tango Lesson (1997), the intricate period costumes of Orlando, and the overt passion in Yes (2004). That tendency is in stark contrast to a lot of your contemporaries—you know, serious independent female-centric films, as well as general British miserablism.

SP: It’s simple: I’ve always thought of myself as an entertainer. I’m in avant-garde show business, whatever you’d like to call it. I want people to enjoy, to soak themselves in different kinds of beauties and pleasures, and feel enlivened by that. Not bored, but nourished. And that takes a great deal of attention to craft. So everything I’ve just been saying about politics, it’s all true. But I don’t just sit around thinking about politics. I’m much more likely to think, “Is this color, right? Is this music gonna go here? How could this shot move? What do we think about the light here?” It’s all the tons and tons of details that go into making up this incredibly sensual experience of the hybrid form known as cinema.

VL: I once interviewed Yvonne Rainer, who like you trained in dance and performance art rather than film. She was doing expanded cinema stuff before she went on to feature films, and there are certainly a lot of parallels between your filmographies. She told me—I’m paraphrasing this badly—that unlike choreographing dance, she doesn’t really understand acting, that it’s this totally mysterious thing to her. Because you can say, “Okay, move your arm like this,” and the dancer will move in that way. But acting doesn’t work like that. Do you feel that way, too? Or has your background in choreography influenced your communication with actors?

SP: Choreography was where I learned about how you move bodies through space, how you work with the whole body, rather than a face, and how you understand movement in every single sense. The essence of cinema is apparently movement, according to André Bazin. There’s no better way of understanding how bodies move, but how the camera moves, or is still—stillness being a huge part of movement—than choreography. So that is true. But I’m completely at ease with a way of working that is from the inside, that is not visible or choreographed, whose expression is in this thing called acting, performing, whatever. I love working with actors on the invisible world. Choreography is, in a sense, the formal language of movement, the organization of movement within the frame, or movement of the frame itself, whereas acting is more like the choreography of interior life that, as its final form, expresses what is visible, unhearable, in the actor’s body and voice.

VL: Rhythm plays an important role in your work across multiple media—you’ve written and arranged music; you’ve written poetry, and Yes is written entirely in iambic pentameter; and then there’s the drumming in your new short film, Look at Me (2022). Beyond the fact the main character is a drummer, the rhythm and progression of Look at Me is so clear. The film came out of The Roads Not Taken (2020), but how did you build out or generate that idea?

SP: Well, in The Roads Not Taken, it’s all in the title: the choices that one makes in life that could have led one down a different road, and what happens to that part of the self that, at least in the world of the imagination, carries down the road you didn’t take. I took that idea for a walk and I wrote initially five or even six different roads not taken by the lead character [played by Javier Bardem]. I ended up shooting four, but one of them was always like a road apart. The other three were kind of interlocking, so you could feel that the road not taken would at some point coincide with the road that was taken. When I was shooting this story, the one with Chris Rock, I thought, “Oh my God, this doesn’t really work with the others, you know what have I done?” But I loved making it. Each story was shot separately, like, four days very quickly. In the cutting room, it became clear to me that this is a separate film. Oh, my God. I’ve got this out—oh, God! So I cut it out and put it to one side, to return to later. I thought of it as having absolutely nothing to do with The Roads Not Taken. And indeed, it has nothing to do with. It is its own story.

Look at Me (2022)

VL: In the ’80s, while attempting to make Orlando, you made The London Story (1986), which is a satire of a spy thriller. And there’s an element of comedy, let’s say, in Look at Me. How do you see yourself in relation to genre? Or comedy in general? Is it of interest to you? Would you like to do something that is purely just for laughs, so to speak?

SP: Well, with The Party, I deliberately set out to allow myself to let go in that area, not restrain myself, and not make something self-consciously sincere. To allow a sort of wickedness to be there, for taboo thought to be there, and for it to be funny. I hoped it would be funny, because it was making me laugh. Then when the actress first read it to me, we were all laughing. But still through the whole edit, I thought, “Oh God, but is an audience going to laugh?” So I did a test screening and people laughed—o much that I couldn’t hear the soundtrack anymore, so I had to create some additional little pauses. That was great as far as I was concerned.

I love working with humor. It’s very difficult, technically. I’m very admiring of comedians. It’s one of the reasons I wanted to work with Chris. The timing and the delicacy of it all, and how far you can tip something into laughter and then it becomes not-laughter anymore, and all that. I’ve written another [film] that I hope to shoot next year, which is not in the same genre, but which I hope will have laughter embedded in it.

VL: When I think of The Party (2017)—I mean, this is true of a lot of your work, you have a lot of films that were ahead of their time, which I know is a silly phrase, but it’s true—I’m focused on the fact that these are people who are almost purely defined by their political views, in a way that wasn’t entirely true when the film came out, but now it’s very true. It’s not like people didn’t have politics then, but now politics are a part of identity in a way that is aggressive and inescapable.

SP: That’s really interesting. I’ve learned that, to my cost, quite often I’ve been about five to 10 years too soon. For example, Rage, you know, was the first ever film deliberately made for people to be able to look at on their phones. At the time, unfortunately, there were less than 12,000 phones in the world that could receive it. So the technology just wasn’t there. And people said to me, “Nobody will ever watch your film on their phones, this is a ridiculous idea. This is going nowhere.” Ho! Ho! Ho! This has happened quite a few times to me, which is odd. But then I feel the writer’s job is to put your ear to the ground and hear the distant rumble, much more than to look out there and see how things appear to be. You can feel the earthquake coming before it breaks.

VL: It’s interesting that Rage is going to be re-presented in a theater now, when everyone watches films on their phones, because even though it’s shot for a phone, the things that are going on with form are fascinating. I think it’s generative, putting what is meant to be seen on a tiny screen onto a big screen, as opposed to the other way around.

SP: Well, I did shoot for both screens. I shot it with these very plain color backgrounds, because I thought it’d be the clearest rendition for a small screen. But I graded it, timed it, and it looks beautiful on a big screen, actually.

VL: Yes, and what you do to the various characters’ faces with that lighting is sort of like what Warhol did with the Xeroxes of photographs that he used for prints—the brightness gets rid of all the wrinkles, and it gives everyone high cheekbones and a “nice” nose.

SP: It’s very flat frontal lighting, shot against a green screen. And then the colors generated in the background were taken from a detail in a person’s face or body. Indeed, it was done as a fine artist would work with the silkscreen print.

Rage (2009)

VL: The fashion world in Rage connects to The Tango Lesson, which is the film that you—or your character—was struggling to create. I really love The Tango Lesson because it shows what is so rarely shown: a woman being creative, in the act of creation, making decisions; a woman who has created in the past tense, having made the film we’re watching. This emphasis on the act of creation and the creator was especially rare in the ’90s, which was the height of the notion of “the death of the author.” Could you discuss the evolution of that film?

SP: While I was making Orlando I was struggling with the—I use the word “struggle” advisedly here—with the fact that the whole story is set in this aristocratic, landowning class universe. Obviously, Virginia Woolf was working satirically, but it’s a very, very contradictory story to work with. As light relief, for my immersion in the Bloomsbury set mentality—by reading everything Virginia Woolf had ever written, and reading everything anybody else has ever written about Orlando in order to really understand what she was trying to do with it—I went off to learn ballroom dancing. I thought that I needed to do something that is a working-class form of populist—and at that point, much mocked—dance. Not ballet, not modern dance. Real old-fashioned waltz, quickstep, salsa, you know? But while doing that, I also learned a little bit of Argentinian tango, and realized that I wasn’t learning the real thing. I managed to find an Argentinian tango teacher in London, the only one. Then eventually he said, “Sally, you need to go to Paris and take lessons from this guy [Pablo Verón].” This was all private, had nothing to do with my film life. I thought of it as something I was doing completely on the side for my own physical and mental health. And then I went to Argentina, and whilst I was there, I started filming a few lessons, and thought, “I’ll make like a little documentary about the tango,” because what I was discovering in Argentina was so different than what everybody’s image of an Argentinian tango is—you know, sleazy, sexy stuff. Because actually it’s a meditation for two. So this 10-minute documentary started to grow. I was taking more lessons, and getting embedded in the experience, and I thought, “Well, the only way I can really make something interesting about this is to use my own body as the kind of medium.” It went from there.

I was very afraid people would misinterpret it as gross artistic narcissism. Friends of mine would tease me and they’d say, “Oh, you’re making a film called This Is Me Dancing with Pablo, This Is Me Dancing with Gustavo.” And I would laugh and laugh and laugh with them. But inside, it was sort of quickening. I told myself, “No, this is in the tradition of collapse. This is in literature, and so many writers who’ve included themselves in the first person, using their name as an alter ego or possible other self. This is in the tradition of Cindy Sherman, and artists who use their own body as a kind of doppelganger of the self. This will just be me in the film, being a person with my name, so it’ll be a double bluff situation,” I thought naively. Of course, they’ll know it’s not really me. How could I be so wrong!? [Laughs] So indeed, I was accused of gross acts of narcissism by some. But on the other hand, it also became a real cult film, playing for like two years nonstop in Paris, where people loved the romanticism of it.

It was an amazing experience. It was also a very difficult and educative experience, to be on both sides of the camera. In particular, experiencing the extreme vulnerability of the performer in trying to do their best when they haven’t gotten the nice kind eyes of the director looking at them. It was very lonely because I had nobody to turn to to say, “Help me be better,” or “Do I look alright?” or “What should I do here?” I really was thrown back on my own resources. The only yardstick I had was: Does that feel true? Is this authentic? What I am doing here? In the end, analytically I could say: this is a film about a process of its own making, and we eventually realize the film this person wants to make is the film we’ve been watching. Very simple. It’s also about somebody exploring another culture that is not their own, but for which they have great love. That is incredibly topical at the moment, in terms of how do we relate to other cultures.

VL: Yes was something you wrote as a response to 9/11, and this insane period of forever wars that we are currently in, as an attempt to engage with and understand other cultures. In order to promote the film, you started a blog and created message boards where people could respond to you directly—again, things have become mainstream now, particularly the idea of constantly interacting with fans. But you’ve chosen not to participate in social media.

SP: As of a week ago, I’ve changed. After years of silence on social media, I’ve decided to open my arms wide, and see what I can do. I don’t allow myself to look because that way, addiction and madness lies. Glimpse, you know, have a little peek. But it’s in order to put out more and to see what happens.

" THE WRITER’S JOB IS TO PUT YOUR EAR TO THE GROUND AND HEAR THE DISTANT RUMBLE, MUCH MORE THAN TO LOOK OUT THERE AND SEE HOW THINGS APPEAR TO BE. YOU CAN FEEL THE EARTHQUAKE COMING BEFORE IT BREAKS."

VL: Do you envision yourself exploring via, let’s say, TikTok or other shorter online projects?

SP: Well, I mean, making this short film, we’re at 16 minutes, which by TikTok standards is ridiculously long, but it did remind me of the changing nature of duration, for absorption of the moving image, and how generationally cut that is. Most of the younger people I know only get their news from social media, looking at things and absorbing the information very fast. They’re very, very quick. It’s not just that they have a short attention span, it’s that they get information fast—a kind of quickness of awareness. And that, I think, is really interesting: the flexible absorption of different kinds of duration, and how people are, in a way, in a constant state of montage. I’ve found my own films mashed up and rejigged and remixed and everything on YouTube, and I always think, “Oh, that’s great! How interesting!” I prefer to be open, and try to be aware of how people are absorbing the moving image. I’m not interested in being nostalgic. I was very happy to embrace digital filming, although I loved filming with film, and I loved cutting on film. But now I also love digital work, and [want] to see where it goes really. I don’t think the feature film form is dead. It still holds this classical shape that endures.

I was just at the Telluride Film Festival for the unveiling of the remastered version of Orlando. I watched it with audiences who were largely young and hadn’t seen it before. The fact that it was made 30 years ago was completely irrelevant. It could have been finished last week, as far as they were concerned, because to them it was new. And it looked new, and incredibly topical—somebody changing sex halfway through? And living in China? Excuse me, you thought about this 30 years ago!? It’s like, yes, Virginia Woolf. Anyway. But a film like that, if it’s made in a certain way, will endure. That’s hard to imagine with a lot of TV series, for example.

There’s a place for that shaped, refined experience, approximately an hour and a half to two hours—any longer not necessary, in my view anyway—that kind of shape that you can live through and that will stay with you as a whole in your consciousness somewhere. That’s extraordinary, to work with that form. So it doesn’t lose out. But what, 16 minutes suddenly? Or 30 seconds? Wow, that’s interesting!

VL: My interest in this comes from the fact that popular narrative film has largely remained the same since the 1930s on a formal level. Close-ups are used in a very particular way, shot/reverse shot, the 180 degree rule—all these conventions, and imparting narrative information, have stayed the same. When I’m thinking of moving things forward, I feel like your films and your formal concerns have really aspired to push things in a new direction, to experiment and see what is possible with narrative. What is the guiding principle in creating that formal play and progression? Do you set out with the intention of breaking new ground?

SP: Usually form follows function. If I feel there’s some idea that I’m really wrestling with, that I want to find a way of embodying, it’s like, well, how can I do that? So it’s more that kind of rumination, rather than, “I’m definitely going to be original and break new ground here.” With Rage, for example, I was getting fascinated by—it’s hard to believe this now, but at the time, it was the beginning of people doing selfies, right? Now, selfies are so ubiquitous, they’ve actually only been around for about 15 years. Everything was being shot the length of a person’s arm? Suddenly, the world is closer, and at a particular kind of angle.

I thought okay, if I’m going to make something that is as if being made by this child, it has to be within that aesthetic, because that is what has been burned into the retina of this person. So everything needs to be shortened, closer, handheld, and so on. But when do you see a film that’s shot entirely and close-up? So suddenly, that’s like new syntax… The desire for new forms is the consequence of form follows function. But it’s also excitement. It’s like, ooh, oh, that would be great! It’s this completely sensual, playful thrill. Working with the medium of film, or whichever thing that has suddenly called, always feels terribly exciting to me to do. It comes from that impulse.

VL: Finally, because we kind of have to, because it is the dominant narrative film at the moment: superhero films. Marvel films have this very specific lack of spatial awareness that you would not expect from an action movie. They’re very flat, very desexualized. Has anybody been in touch with you to direct one? They’re always desperate for female directors.

SP: No, they haven’t. I don’t think I’d be a very good contender, because I don’t really watch them as part of my ecology of time, and about how I’m going to spend my life. People have, to some degree, given up on approaching me for anything [laughs] because I have a 100 percent record of turning everything down. I’ve always got something I’m writing, or I’m in the middle of doing, that I’m very passionate about. I live in hope something fascinating might pop in through the door. It’d be interesting. But on the whole, it’s the journey from complete authorship or from complete nothingness—this thing didn’t exist at all in the world before I started building it, image by image, moment by moment, until it’s whole. And then: Oh, my God, there it is… is that complete? That is so exciting. I imagine it’s harder to come in later, when the ideas have already been worked out by somebody else. Although I remember I was with this one director who said, “Yeah, but that’s where the heavy lifting is.” It’s great if you can come in after that has been done, and indeed, the heavy lifting is the writing. That is the heavy lifting. Yes.

read the piece here: https://metrograph.com/the-pio...

Continue readingSally Potter in Document Journal

Ahead of a retrospective at the Metrograph, the legendary filmmaker reflects on her groundbreaking adaptation of the Virginia Woolf classic

As the poet Sina Queyras wrote of Virginia Woolf earlier this year: “If I close my eyes, I see bodies tumbling through time. I see many bright colors, textures, pleasures, sounds—it is a bacchanal of sensations, [Woolf’s] vision. And through it she stitches a firm line.”

Something similar could be said of the film Orlando (1992), adapted by British filmmaker Sally Potter from Woolf’s 1928 novel of the same name. Considered a landmark in queer and feminist film studies, as well as a breakout role for Tilda Swinton, Orlando celebrates the fluidity of both time and gender, tracking the life of the immortal Lord Orlando across four centuries of British history, during which time Orlando also becomes a woman. Woolf’s source material is one-part extended love letter (to Vita Sackville-West, with whom she had an affair), and one-part satire of British culture and its patriarchal traditions of property, inheritance, empire, and marriage. In Potter’s hands, the story of Orlando indulges in a postmodern—even parodic or camp— sensibility, set to the tune of a score that she co-composed. It is a sensory feast—a propulsive, vibrant, playful adaptation that continues to enchant 30 years later.

On the whole, the films of Potter are films that think—they are not satisfied simply to ‘represent’ ideas on the screen, but must wrestle with them, actively, at every level from style to performance. Potter’s work dates to the late ’60s London Film-maker’s Co-op and a subsequent career in choreography, performance art, and theater. Despite her move into narrative features in the late ’80s, however, her taste for experimentation has never waned, even as she has migrated somewhat closer to the ‘mainstream.’ From the iambic pentameter of Yes (2004), to her self-reflexivity and self-representation in The Tango Lesson (1996), to directing the first feature film conceived to be watched on a mobile phone with Rage (2009), Potter’s cinema is morphing, responsive, and uncompromising, unwilling to be easy, and never predictable.

In recognition of Orlando’s 30th anniversary and a major retrospective of Potter’s work opening at Metrograph, Document spoke with Sally Potter about the challenges of adaptation, the legacy of gender and sexuality in film, and how it lives in cinephiles’ minds today.

Tia Glista: What was your relationship to Woolf, and to Orlando more specifically, before you began this project?

Sally Potter: Well, my relationship to Virginia Woolf was one of admiration and intimacy. I think every reader has a very intimate relationship with a writer that you read again and again. You enter their world. Their world enters you. It’s a sort of private space, the reading space, and I was an avid reader as a child and teenager. I still am an avid reader.

I do remember reading the book as a young teenager. I’m guessing fourteen, something like that, and being very, very affected by it—visually, emotionally. The world of ideas that she was presenting excited me, and when I later came to read her diaries and all the other things she had said about writing Orlando, and about how it was received, and all the rest of it, I was fascinated by how she described it visually as wanting to exteriorize consciousness; in other words, find images that would somehow illuminate the way the way the mind works.

But Orlando was, when it came out, trivialized by critics. It was rather light and so on. But it’s not. It’s a serious exploration of ideas with a light touch. And because it was difficult to raise money for the film (and I mean very, very difficult), in the end meant that I had a lot of time— time I didn’t necessarily want—but it gave me time to revise and revise and revise the adaptation, and to figure out really how how to do it, how to turn it into a film.

Tia: I’ve read that you always felt you could visualize the book as a film—what specific images were the most vivid for you, and did any of them make it into the final version?

Sally: The apple seller frozen in the ice, with the apples suspended in the ice around her. That image stayed with me very strongly, and in the end it’s the first thing I shot when I came to shoot the film, and it was obviously very difficult to figure out how to do it, because this was before the days of CGI, so I shot it with a stunt woman in a swimming pool… I think in many ways it was that image that triggered the film. Why that image, I think, is so particular. There’s something about the apple that is sort of mythic, and of course the brutality of this working woman trapped under the ice, being laughed at as this spectacle by the men who are looking down. Because it’s just an image for them, you know. So it felt to me like there was so much going on in that image. That’s where it started.

Tia: This is a film with so much intricate movement, right from the first frame. There is ice skating, and dancing, and that iconic sequence of Orlando’s run through the maze in which she bursts from the 18th-century into the 19th-century. How does your background in dance and choreography come to bear on your filmmaking?

Sally: Hugely. I think first of all, anybody who’s studied dance knows about work and actually how much you need to work to improve. You know you don’t kind of hang around waiting for inspiration. You just go to class every day, and it’s very pragmatic. Anybody who’s done choreography knows what it’s like to stand there thinking, ‘Hmm. Should somebody cross from right to left or left to right or come closer, or be further away? Should this be fast, or should it be slow? And are they far or are they near? Are they at speed? Are they changing direction?’ All those choreographic questions are decisions that, as a director, I’m making all the time. And I’m absolutely sure that all the work that I did as a choreographer, and in performance, and with my own body, informs how I work as a director.